you-win: API Reference

Importing

you-win exports the following names:

To import all these names so you can use them in your code, use the following lines:

const uw = require('you-win')

const {Phone, World, Sprite, Text, Polygon} = uw

Assets

Before you can do anything, you need initialise you-win. You do this by calling uw.begin(), which downloads all the files your game needs. We display a progress bar while your files are downloading.

await uw.begin()

The special await keyword is important here: it tells the computer not to carry on with your program until everything has finished loading.

You should call begin() exactly once.

Costumes

A costume is an image that controls how a Sprite looks.

You download them by calling loadCostume() with a name and URL, before you call begin().

If you make a static folder in the same place as your game’s .js file, you can put images inside it, and then use '/<filename>' to load them. For example, if you put my-asteroid.png in the static folder:

uw.loadCostume('asteroid', '/my-asteroid.png')

await uw.begin()

You can also use assets from a Glitch project. Copy their URL into your program:

uw.loadCostume('face', 'https://cdn.glitch.com/f213ed6a-d103-4816-b60d-47c712a926e2%2Fcat_00.png')

await uw.begin()

⚠ Because of security restrictions, you can’t use just any image URL from any website.

To use a costume later, give its name:

var s = new Sprite

s.costume = 'asteroid'

If you load more than one costumes, you-win won’t wait until the first one finishes downloading before downloading the next one. It speeds things up by downloading them all at once (i.e. in parallel).

uw.loadCostume('duck1', '/duck-frame1.png')

uw.loadCostume('duck2', '/duck-frame2.png')

await uw.begin() // waits for duck1 and duck2 to finish downloading

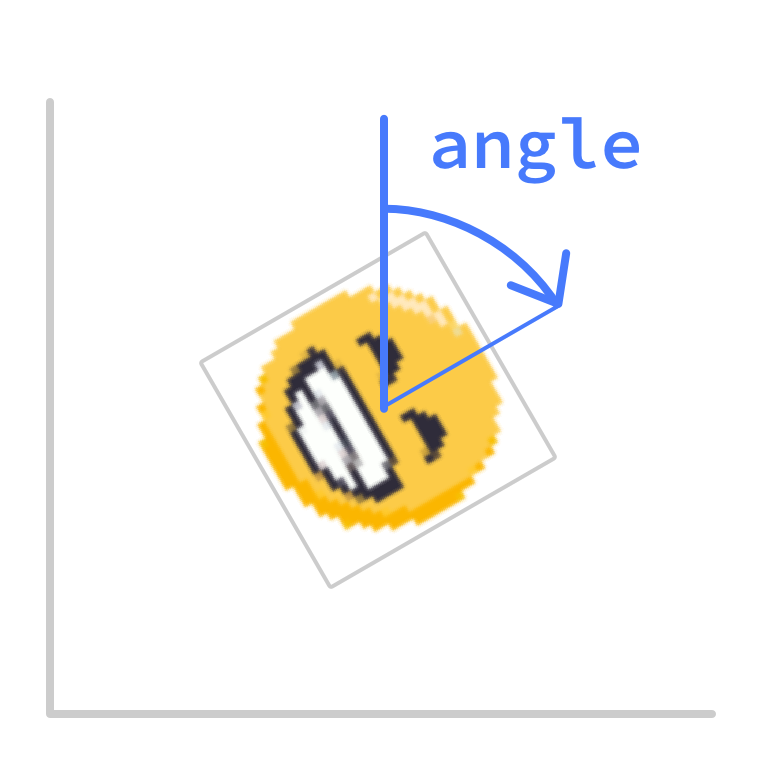

Emoji costumes

Emoji costumes are loaded by default. To use them, just set your Sprite’s .costume attribute to an emoji string:

var s = new Sprite

s.costume = ' '

'

The emoji costumes are sized 32x32 pixels. Most but not all emoji are included.

Emoji make great placeholder graphics for your game, or even final graphics if you like the retro pixel-art theme.

You can also use emoji inside Text.

World

World sets up the screen, manages all the sprites, and emits events such as taps and drags on the background.

Set up the world after calling begin() to load your assets.

// Load everything we need

await uw.begin()

// Make the world

var world = new World

world.title = ''

world.background = 'white'

// Now we can start making Sprites!

It has the following attributes:

world.width/world.heightThe size of the game’s visible area on the screen.

If you don’t provide a width or height when making your world, it will default to using the size of the phone’s screen.

world.scrollX/world.scrollYAn offset applied to all of the objects on-screen.

You can change these in order to move around the virtual “camera” to show different parts of the world, e.g. for writing a platformer.

But be aware, the X and Y positions of your sprites won’t change when you scroll; so a sprite at (0, 0) will no longer be in the bottom-left corner of the screen!

world.backgroundThe background colour of the world. Uses HTML/CSS colours, such as

redor#007de0.

World has the following methods:

world.stop()

Sprite

A Sprite is an image in the world that can be moved and rotated and so on.

To make your Sprite appear, you must set its costume.

uw.loadCostume('cat', 'https://cdn.glitch.com/f213ed6a-d103-4816-b60d-47c712a926e2%2Fcat_00.png?1499126150626')

await uw.begin()

var world = new World

var cat = new Sprite

cat.costume = 'cat'

var bigCat = new Sprite

bigCat.costume = 'cat'

bigCat.scale = 2 // twice as big

Sprites have quite a few attributes which you can change. You can also set their initial values when you make the sprite.

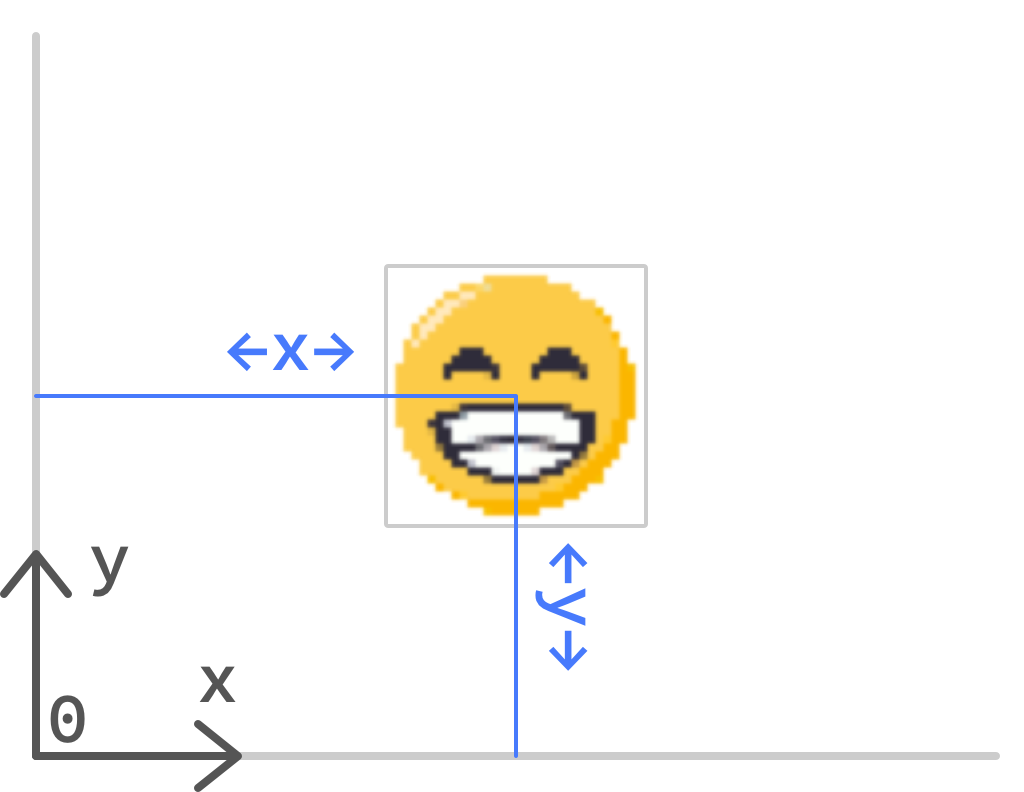

sprite.posX/sprite.posYThe X and Y co-ordinates of the center of the sprite, starting from the bottom-left corner of the screen.

sprite.angle = 0The rotation of the sprite, going clockwise.

sprite.scale = 1.0The scale factor of the sprite.

1.0means 100%;2.0is twice the size;0.5is half the size.sprite.flipped = falseEither

trueorfalse.Whether to flip the sprite’s costume, so that it faces the other way. Defaults to `false.

sprite.opacity = 1.0Controls the sprite’s opacity aka. alpha aka. transparency aka. “ghost” effect.

A value of

1.0means the sprite is fully opaque;0.0means the sprite is fully see-through.If you want to remove the sprite entirely and permanently, use

destroy().sprite.costume = 'poop'The image to use for the sprite, in case you want to change it later. For example, if you want to cycle between several images in order to “animate” the sprite”.

You can also give an emoji here, to get one of the built-in emoji costumes (assuming

you-winsupports that emoji).sprite.left/sprite.right/sprite.top/sprite.bottomThe co-ordinates of the edges of the bounding box of the sprite. The bounding box is an axis-aligned box enclosing the whole sprite.

TODO: diagram

These can be useful for getting or changing the position of the edge of a sprite. They tend to be more useful for non-rotated sprites.

Important: you usually need to assign these last. If you set the the position of an edge, and then for example change the

scale, the edge won’t line up anymore! So make sure you set edge positions after setting the other attributes.

Sprites have some useful functions attached to them.

sprite.raise()Bring the sprite to the front, so that it is above all the other sprites.

sprite.lower()Send the sprite to the back, below all the other sprites.

sprite.getTouching()Returns a list of sprites which are overlapping this one.

Useful for detecting collisions!

for (var other of player.getTouching()) { if (other.isBullet) { // lose some health } }sprite.getTouchingFast()The same as

getTouching, but avoids the accurate-but-slow Scratch-like pixel-perfect collision detection, which compares the images of the two sprites pixel-by-pixel.sprite.isTouching(otherSprite)Returns

trueif the two sprites are overlapping;falseotherwise.sprite.isTouchingFast(otherSprite)The same as

isTouching, but avoids the accurate-but-slow Scratch-like pixel-perfect collision detection, which compares the images of the two sprites pixel-by-pixel.sprite.touchesPoint(x, y)Returns

trueif the point overlaps the sprite;falseotherwise.You probably won’t need this, but it can be useful if you’re doing complicated things involving

dragevents.sprite.isTouchingEdge()Returns

trueif the sprite is near to the edge;falseotherwise.sprite.isOnScreen()Returns

falseif the sprite is completely off the screen;trueotherwise.This takes into account scrolling.

sprite.destroy()Remove the sprite from the screen. Afterwards, the sprite is “dead” and you can’t use it anymore.

If you just want to hide the sprite for a moment, set its

opacityto zero.

Sprite::forever

forever is really useful function: it lets you do something on every “frame” or “tick” of your game. Usually ticks happen 60 times a second (60 FPS).

Write a forever block like so:

sprite.forever(() => {

// do stuff

})

Any code after the forever loop isn’t affected:

sprite.forever(() => {

// This code runs forever.

})

// This code runs once.

// Carry on setting up the game:

var otherSprite = new Sprite

When the Sprite is destroyed, the forever loop will stop.

If you want to stop a forever loop without destroying the Sprite (so that it doesn’t run forever!), you can return false:

player.forever(() => {

if (player.isTouching(floor)) { // the floor is lava

// game over!

return false // stop this loop

}

// otherwise, move the player...

})

Text

A Text object is like a Sprite, but instead of a costume, it’s used to display text.

var label = new Text

label.text = 'SCORE: ' + 100

The text has a retro aesthetic. It also supports emoji (using the same emoji set as Sprites can use). Which means that this:

var snowy = new Text

snowy.text = ' '

'

…is quite similar to this:

var snowy = new Sprite

snowy.costume = ' '

'

Text objects have all the same attributes as a Sprite–but instead of a costume, they have the following:

obj.textThe text to display.

obj.fillThe color of the text, e.g.

text.fill = '#007de0'

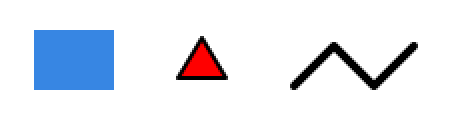

Polygon

A Polygon is like a Sprite, but has a shape instead of a costume. This shape is defined using a list of points. Examples include making a filled rectangle, a triangle with a fill and an outline, and thick lines.

Here’s an example Polygon:

var p = new Polygon

p.points = [[0, 0], [0, 32], [32, 32], [32, 0]]

p.fill = '#007de0'

p.outline = 'black'

p.thickness = 2

Polygons have all the same attributes as a Sprite–but instead of a costume, they have the following:

polygon.pointsA list of points. Each point is a 2-element list with the X and Y coordinates (relative to the polygon’s center), like so:

p.points = [[0, 0], [-16, 20], [16, 20]]polygon.fillThe color painted inside the shape, e.g.

polygon.fill = '#007de0'.Leave out this setting, or set it to

null, for no fill (just an outline).polygon.outlineThe outline color, e.g.

polygon.outline = 'black'.Leave out this setting, or set it to

null, for no outline. You must specify either a fill or an outline (or both).polygon.thicknessHow thick to draw the outline (in pixels). Defaults to 2.

polygon.closedWhether the last point should be joined to the first one, to make a closed shape.

Defaults to

truefor filled polygons. TODO: saner default handling.

Rect

A Rect is a special sort of Polygon which, unsurprisingly, is shaped like a rectangle.

Instead of a costume, Rects have the following:

rect.width/rect.heightThe dimensions of the rectangle.

rect.fill/rect.outline/rect.thicknessThe fill color, outline color, and width of the outline.

See Polygon for more details.

Don’t forget you will need to use new Rect and not new Polygon

Touch Events

An event tells you that something has happened. Both Worlds and Sprites will emit events when they are tapped or dragged.

If a tap overlaps more than one sprite (because the sprites are overlapping), then the sprites are told about the events in order. The front-most one sees the event first.

If a sprite wants to handle an event, it should return true. From then on, no other sprites (nor the world!) will see the event.

There are a few kinds of event:

world.onTap(e => { ... })/sprite.onTap(e => { ... })A

tapevent happens when a finger is pressed against the screen and let go without moving.The event object

ehas the following attributes:e.fingerX/e.fingerY: the coordinates of the tap.

world.onDrag(e => { ... })/sprite.onDrag(e => { ... })The event object

ehas the following attributes:e.startX/e.startY: the coordinate the drag started from.e.deltaX/e.deltaY: the amount the finger has moved since the last drag event.e.fingerX/e.fingerY: the current coordinates of the drag.

If the Sprite doesn’t want to hear about the event anymore, it can

return false.world.onDrop(e => { ... })/sprite.onDrop(e => { ... })

If you’re testing your game on a computer, mouse clicks and drags will work to simulate touches – but remember that unlike fingers, a mouse pointer can only be in one place at a time!

Detecting taps

world.onTap(e => {

// make a ball where you clicked

var ball = new Sprite

ball.costume = 'beachball'

ball.posX = e.fingerX

ball.posY = e.fingerY

ball.onTap(e => {

// flip

ball.flipped = !ball.flipped

// handle the event

// - otherwise another ball will get spawned!

return true

})

})

Dragging sprites around

var ball = new Sprite

ball.costume = 'beachball'

ball.onDrag(e => {

// move when dragged

ball.posX += e.deltaX

ball.posY += e.deltaY

return true

})

Touches list

Detecting fingers held down

Sometimes you don’t want to listen for events: you just want to know where fingers are touching the screen, right now. To do this, you can use getFingers().

world.getFingers()Returns an

Arraycontaining a list of each finger currently touching the screen.You can use a

for...ofloop to go through each finger in turn:for (let e of world.getFingers()) { if (e.fingerX < world.width / 2) { // touching the left side of the screen } else if (e.fingerX > world.width/ 2) { // touching the right side of the screen } }Each finger is an event object, just like the

eargument passed toonTaporonDrag.

Phone

Phone provides access to sensors on a smartphone, such as the accelerometer. You can use this to control your game depending on how the phone is held; for example tilting to steer in a racing game.

You need to make a Phone object before you can access the readings:

var phone = new Phone

It has the following attributes which you can get:

phone.zAngle: the angle of the phone’s screen in relation to the ground.An angle of

0means the phone is held upright. Tilt the phone to see it change.

Sound

To use sounds, make sure to import {Sound} from 'you-win'.

To load a sound , use loadSound. See Assets for details on the static/ folder and where to put your sound files.

uw.loadSound('moo', '/moo.wav')

await uw.begin()

Before you can play your sound, you must create a Sound object.

var mooNoise = new Sound('moo')

Finally, you can play your sound at the appropriate time.

mooNoise.play()

Maths

Some built-in maths utilities.

uw.range([start], end, [step])Return a list of numbers starting at

start(default0), and ending beforeend. Behaves identically to Python’srange().The optional

stepargument (default1) is how much to move between each item.uw.range(5) // => [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] uw.range(5, 10) // => [5, 6, 7, 8, 9] uw.range(10, 20, 2) // => [10, 12, 14, 16, 18] uw.range(0, -5, -1) // => [0, -1, -2, -3, -4]uw.dist(dx, dy)The distance between (0, 0) and (dx, dy), calculated using Pythagoras’ Theorem.

Some trigonometric functions. These work in degrees, unlike the ones built-in to JavaScript which use radians.

uw.sin(deg)uw.cos(deg)uw.atan2(x, y)

Random

Some built-in ways of getting random things are included.

uw.randomInt(from, to)Return a random integer (whole number) between

fromandto, inclusive.uw.randomInt(1, 3) // => 2 uw.randomInt(1, 3) // => 1 uw.randomInt(1, 3) // => 3uw.randomChoice(array)Return a randomly-selected item of an array.

uw.randomChoice([' ', '

', ' ', '

', ' ']) // => '

']) // => ' '

'